City Parking: Private Sector Cash Cow or Public Good?

Even a casual reader of UrbanTools knows that the concept behind land taxation is to encourage free markets and return economic vitality to cities while keeping revenue flows intact for community needs.

Yet – again and again – cites with good development ideas (and land tax proponents) have run into opposition from the parking “industry” that often stymies reform for the greater good. How does this happen?

As experience in Philadelphia has shown, flat-top parking lots are a business model that leach off productive neighbors and also corrupt the decision-making and political process. Private parking lots enjoy higher profit margins than their neighbors that invest in plant, employment, and marketing while paying taxes on most of their activities. With taxes on their vacant land nearly non-existent, parking lot owners have a jump on actual corporate and human citizens.

When a parking lot becomes unable to handle the traffic generated by their hard-working neighbors, a parking deck is sometimes built, usually with abatements and exemptions that established businesses (not to mention hard-pressed neighborhoods) cannot enjoy.

These conditions leave the parking lot owner with lots of surplus cash. Again, in Philly, this leads to showering the political system with money, muting the voices of mere citizens. One company, with a now near-monopoly on parking in Center City, is one of the most significant contributors to political campaigns.

Effect on the Local Economy

When a parking lot becomes unable to handle the traffic generated by their hard-working neighbors, a parking deck is sometimes built, usually with abatements and exemptions that established businesses (not to mention hard-pressed neighborhoods) cannot enjoy.

Some have argued that these decks, at the very least, employ many who would have a hard time getting work. Untrue: while it’s evident that a lot uses a sprinkling of employees on a site meant for hundreds of productive workers, the modern parking industry is working fast to eliminate workers from its bottom line. Automation of parking and payment has led to slashed jobs and stagnant pay.

A parking lot in a bustling older downtown means one thing: a building once stood where asphalt is now king. Each building lost is a loss to the tax base of the city in many ways: property tax, business tax, wage tax. The current system of taxation does not recoup the high land values associated with these now barren sites.

In Philadelphia, there has been a consumer resentment building for years against the high rates charged by the near-monopoly of parking. With no competition for rates, only the most high-end retail can justify a shopper, especially from the suburbs, paying $20 to $25 an hour for a hammer, a bra or a lunch. Add to this an under-attended lot or deck becoming a magnet for smash-and-grab thieves we have a formula for a consistently under-performing Business District, all thanks to the “industry” that feeds from it.

Low taxes on the parking industry also discourage the use of mass transit, a huge recipient of government investment. A higher tax on parking – or the land on which parking takes place – would have the effect of lowering the rates and reducing the high-profit margin to a level consistent with other businesses in the area. Land value taxation – combined with the fear that it inspires amongst parking lot barons – is a fundamental tool in the struggle against urban economic parasites.

A Public Solution?

One other way to solve this problem may be to consider parking a public good and service. The logic of municipal parking lots and decks is hard to escape: by removing the profit motive, rates reduce to non-extortionate levels. This assistance to responsible and productive shoppers, visitors, and the buildings that serve them would provide a far more cause-and-effect than most of the sweetheart panaceas that city governments hand out.

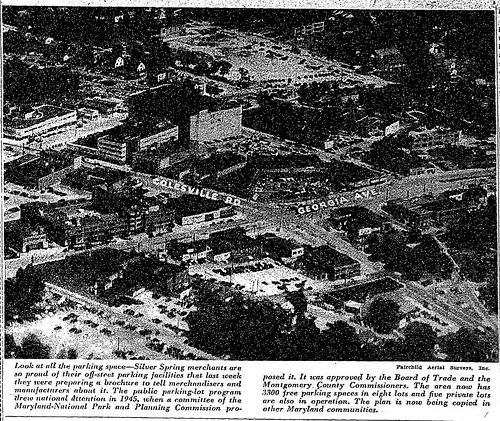

The experience of a visitor to Silver Spring, Maryland is illuminating: rates are low in a series of county-owned decks. The area surrounding the public parking facilities are becoming crammed with shops and offices, serving all needs from modest to Xanadu-esque. This urbanization has (perhaps counterintuitively) evolved into lower use of parking spaces. The Silver Spring Metro stop into DC is one the most utilized in the system but is now its own destination and choice for housing at most price points. That transition would have been far harder if parking were in the hands of parking lot barons.

It’s time for cities to realize the years of decline have reversed. It’s time to seize the destiny of their downtowns back from the parasites and return it to the people and the commerce that can again make our cities great.